By Kathleen Kemsley (c) 2020

The Great Barrier Reef! My dreams of traveling to Australia focused on this place. The largest living creature, visible from outer space, the reef shimmered with colorful fish and miles of coral in my imagination. Now, four days into a solo trip to Australia, I was close to reaching the reef’s southern end.

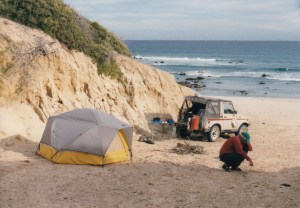

Several hours north of Hervey Bay, Queensland, I turned onto Fingerboard Road, a short cut to the coast posted with Kangaroo Crossing signs all along the way. After scoring the last available site at a beachfront campground, I inquired about joining an excursion to the Great Barrier Reef. The man at the desk kindly made some phone calls on my behalf to secure a space on a boat departing the next morning for Lady Musgrave Island.

I awoke well before dawn, excited to finally meet this creature that I had traveled halfway around the world to see. One of the unspoiled and least crowded places to visit the GBR (as it’s locally known) was from the Town of 1770, on the southern end of the reef. The boat I boarded in the 1770 harbor carried 40 people on a straight shot about 90 minutes east. A couple of blokes from Melbourne sat with me – one silent and the other talk-your-ear-off chatty. The talkative one let me know right away that his marriage was on the rocks. In no mood to listen to his domestic problems, I extracted myself from the one-sided conversation, went outside and climbed up to the railing on top of the cabin where the wind screaming past my ears precluded any further discussion.

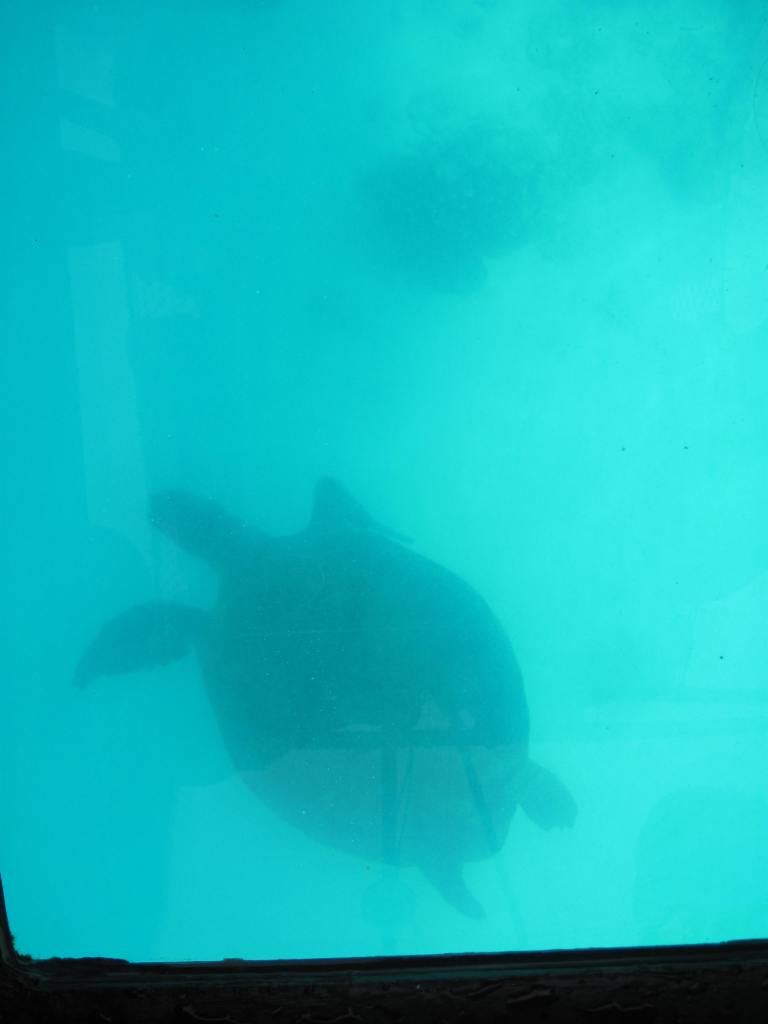

Upon arrival into a protected bay next to Lady Musgrave Island, we split into two groups. Fortunately, the Brothers Melbourne were in the other group, which immediately went into the water to snorkel. My group boarded a glass bottom boat to observe loggerhead turtles next to the reef. They were giants compared to the turtles in my river at home – ancient silhouettes at least three feet long. The man driving the boat, George, said they could hold their breath under water up to nine minutes at a time.

I turned toward him as he continued talking about the life cycle of a sea turtle. In contrast to the other four Millennials who crewed the boat, George was a sun-bleached, bearded older guy. I estimated that he was about my age, 60 – which meant older than almost everyone else aboard.

On Lady Musgrave Island, a national park, I walked through a forest of Pisonia trees, whose branches sagged heavy with the weight of thousands of nesting white capped noddie birds. The beach sand, so white it hurt my eyes, was home to bridled terns and silver gulls. By the time I walked back around the edge of the island, George and the glass bottom boat had fetched the other half of the group and returned. I rode with George back to the main boat for lunch, then finally it was time to meet the GBR.

Immersed in the warm sea, I snorkeled up and down a section of reef near the island for an hour, peering at starfish, jelly fish, sea cucumbers, seahorses, and countless thousands of fish in every color of the rainbow. The coolest creature was a box fish, Day-Glo yellow with black spots, shaped like a tennis ball with nearly invisible fins.

That bit of reef itself was not so different from any other place in the world I’ve been snorkeling. But the mind-boggling fact was the size of the GBR – more than a thousand miles long. It was difficult to wrap my head around the idea of this organism – this animal – living just beneath the water’s surface, breathing and eating and growing, and trying to survive in the warming waters of the south Pacific Ocean.

Exhausted, fingers pruned from extended exposure to salt water, I was the last one to climb aboard the boat. As we started back toward land, I walked outside and perched on a plastic cushion against the stern. George, the bearded crew member, appeared and sat beside me. Just to say something, I asked him how long he had been doing this work, guiding tourists to the reef.

“Up until five months ago, I spent my entire life as a commercial fisherman, he replied. “Then one day I decided it was time for me to hang up my fishing license and begin to give back to the sea instead of taking from it. Someone else isn’t using my license – no one is using it. I still get to be on the sea, which I love, but I’m no longer extracting from it.”

“What brought on the change?” I asked him.

“I was catching these fish that were 75 or 80 years old. It occurred to me that they’re older than me. How long would it take for the resource to replace them? So I decided to stop killing them and instead share their beauty with people who want to see the sea creatures alive.”

He had a big voice and he shouted in my ear to be heard above the roar of the boat’s engine. I tried to answer that as a retired resource manager of America’s national forests, I applauded his efforts at conservation. But my voice failed; all I could do is cough and nod and smile at him.

He went on to tell me about the kangaroo family that lived in his yard. The old wooden sailboat he had rescued from the junk heap and was restoring. And his daughter who had just escaped from an abusive spouse and was building a new life as a single mom in Darwin.

At one point, George asked me where I was from, and I was able to get across that I was an original California girl, fifth generation, in fact, having grown up in Los Angeles. He began to sing that awful Beach Boys song about California girls being the cutest girls in the world. Well, that might have been accurate back in 1974, when I wore a puka shell necklace and a crop top to show off a flat, tan belly. But for crying out loud, more than forty years had passed since then. Now my skin was tarnished like leather, and I had long ago moved — first to Alaska, then to the desert.

George didn’t know all that. “I bet you’re spiritual, not religious,” he mused. Another tired cliché that probably applied to any aging hippie from California. I wanted to change the subject to something deeper. Relate my experience with forest management, or maybe talk about ways to save the GBR. But, since my voice was not cooperating, I just nodded and smiled some more.

Out of the corner of my eye, the Town of 1770 appeared. Reluctantly, George rose and jumped into action to help bring the boat to dock. When I disembarked at the pier, the crew lined up to shake the hands of all the passengers. At the end of the line was George. He grabbed me in a bear hug.

It occurred to me later that I probably could have wrangled an invitation to his homestead with kangaroos on the lawn if I had reached out and hugged him back. But instead, I shrunk away and disappeared into my camper van parked across the street.

A song by Tom O’dell played on my i-Pod during the drive back to the campground, expressing my feelings at that exact moment. “I want to kiss you, make you feel all right, but I’m too tired to share my nights. I want to cry, and I want to love, but all my tears have been used up. On another love, another love. All my tears have been used up.”

This was my first solo international trip since my husband passed away. As of yet, I didn’t have the hang of this traveling-woman-free-spirit persona. Some other time, perhaps on the next trip, I might find the courage to go through with one of those traveler’s love affairs. But this time, it was enough just to feel the warm glow of a shared connection with a man passionate about the Great Barrier Reef.

retreat for himself and his buddies. My great-grandfather, Otto Crain, worked as the first ranch foreman. He arrived with his new bride, Gertrude Kavanagh, right after their New Years wedding, 1909. In a one-room log cabin that October, Gertrude gave birth to their first child, Louise.

retreat for himself and his buddies. My great-grandfather, Otto Crain, worked as the first ranch foreman. He arrived with his new bride, Gertrude Kavanagh, right after their New Years wedding, 1909. In a one-room log cabin that October, Gertrude gave birth to their first child, Louise. commercial center for nearby mining claims. Today it hangs on mostly due to a small but steady procession of two- and four-wheeled explorers traveling the rough dirt roads of the Alpine Loop Backcountry Byway from Silverton.

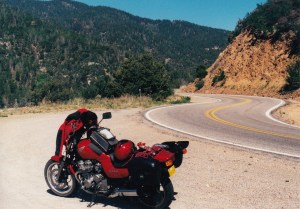

commercial center for nearby mining claims. Today it hangs on mostly due to a small but steady procession of two- and four-wheeled explorers traveling the rough dirt roads of the Alpine Loop Backcountry Byway from Silverton. pulse quickened reflexively, since I have worked for more than twenty years in the fire suppression field. But a helicopter had already been launched and it was working the flames with its bucket, so I didn’t need to stop. A few miles later I reached world famous Aspen. To my right, trees were clear-cut in rows down the mountainsides to accommodate ski lifts and world class runs. Nothing of interest to a motorcyclist in August!!

pulse quickened reflexively, since I have worked for more than twenty years in the fire suppression field. But a helicopter had already been launched and it was working the flames with its bucket, so I didn’t need to stop. A few miles later I reached world famous Aspen. To my right, trees were clear-cut in rows down the mountainsides to accommodate ski lifts and world class runs. Nothing of interest to a motorcyclist in August!! Kavanagh. He, along with his wife Mary and several children, made the difficult trek across country by rail, stage, and foot to reach Leadville in 1882. Austin had some connections with politicians and businessmen from his native Boston, so he established himself as the right-hand-man of a wealthy local businessman in Leadville. Most of their children perished in the harsh conditions at 10,400 ft elevation, but then two more (including my great-grandmother Gertrude) were born in Leadville, growing up fit and hardy in the rough mountain town.

Kavanagh. He, along with his wife Mary and several children, made the difficult trek across country by rail, stage, and foot to reach Leadville in 1882. Austin had some connections with politicians and businessmen from his native Boston, so he established himself as the right-hand-man of a wealthy local businessman in Leadville. Most of their children perished in the harsh conditions at 10,400 ft elevation, but then two more (including my great-grandmother Gertrude) were born in Leadville, growing up fit and hardy in the rough mountain town. pictured my grandmother Louise and her seven siblings wandering around in these woods while their dad raised trout. The Crain family moved here after several years in Creede and lived in a tiny cabin behind the main hatchery building. The hatchery was a peaceful, natural place where I imagined the children would grow up away from the influence of crooked miners and other shady characters back in town. They lived there in apparent bliss, a loving Irish-American family with a new baby arriving almost every year.

pictured my grandmother Louise and her seven siblings wandering around in these woods while their dad raised trout. The Crain family moved here after several years in Creede and lived in a tiny cabin behind the main hatchery building. The hatchery was a peaceful, natural place where I imagined the children would grow up away from the influence of crooked miners and other shady characters back in town. They lived there in apparent bliss, a loving Irish-American family with a new baby arriving almost every year. people’s hard-earned savings. The main street was lined with casinos, attracting people from Denver and Colorado Springs to try their luck on the poker machines and roulette wheels. One of my Ben Franklins disappeared at lightning speed into a one-armed bandit, so I gave up and headed back to my bike to continue my journey.

people’s hard-earned savings. The main street was lined with casinos, attracting people from Denver and Colorado Springs to try their luck on the poker machines and roulette wheels. One of my Ben Franklins disappeared at lightning speed into a one-armed bandit, so I gave up and headed back to my bike to continue my journey. drawback: the rally took place in eastern Kansas. Kansas? What was there to see in Kansas?

drawback: the rally took place in eastern Kansas. Kansas? What was there to see in Kansas? last (or first, depending on whether you were coming or going) view of the Rocky Mountains.

last (or first, depending on whether you were coming or going) view of the Rocky Mountains. trading buffalo robes and beaded clothing for horses. Some conflicts were inevitable, but trail users for the most part cooperated with each other because everyone had something the others wanted.

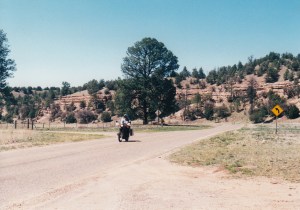

trading buffalo robes and beaded clothing for horses. Some conflicts were inevitable, but trail users for the most part cooperated with each other because everyone had something the others wanted. Our ride on a dirt road back to the highway the following morning was halted for a few magical minutes while a herd of bison passed by. Separated from us only by a cattle guard, they milled around, males sparring half-heartedly, calves chasing after mothers who leisurely grazed on the remnants of long prairie grasses.

Our ride on a dirt road back to the highway the following morning was halted for a few magical minutes while a herd of bison passed by. Separated from us only by a cattle guard, they milled around, males sparring half-heartedly, calves chasing after mothers who leisurely grazed on the remnants of long prairie grasses. tallgrass prairie that once covered 400,000 square miles of the Great Plains. We stretched our legs walking up a steep driveway to reach a ranch home and three-story barn built of hand-cut limestone in 1881.

tallgrass prairie that once covered 400,000 square miles of the Great Plains. We stretched our legs walking up a steep driveway to reach a ranch home and three-story barn built of hand-cut limestone in 1881. it is billed as the oldest continuously operated restaurant west of the Mississippi River.

it is billed as the oldest continuously operated restaurant west of the Mississippi River. Colorado state line. The Santa Fe Trail followed the bank of the Arkansas River, once the southern border of the United States. The railroad, too, followed the trail route next to the river. Ironically, the materials used to build the railroad were hauled on the Santa Fe Trail; once completed in 1880, the railroad then rendered the trail obsolete. But later, when long-haul trucks eclipsed freight trains, the trail route was resurrected and paved.

Colorado state line. The Santa Fe Trail followed the bank of the Arkansas River, once the southern border of the United States. The railroad, too, followed the trail route next to the river. Ironically, the materials used to build the railroad were hauled on the Santa Fe Trail; once completed in 1880, the railroad then rendered the trail obsolete. But later, when long-haul trucks eclipsed freight trains, the trail route was resurrected and paved. reconstructed the building in the 1970s using historically accurate drawings and photographs. As we wandered past doorways of more than 20 adobe rooms on two levels, a historian dressed in period clothing fed a campfire by the fort’s door and answered questions about life on the frontier. The smell of burning juniper added to the authenticity of the restoration at this important outpost on the Santa Fe Trail.

reconstructed the building in the 1970s using historically accurate drawings and photographs. As we wandered past doorways of more than 20 adobe rooms on two levels, a historian dressed in period clothing fed a campfire by the fort’s door and answered questions about life on the frontier. The smell of burning juniper added to the authenticity of the restoration at this important outpost on the Santa Fe Trail.